‘Sometimes a photograph can change someone’s life.’

The only thing I’ve ever learned about war is that everybody pays a price for it. At school, we learn the history of conflict – the dates of wars, the number of casualties – but never of the long-term consequences. Yet war affects the people caught up in it for the rest of their lives, and beyond. The impact can ring across generations.

I became a photographer by accident. At 18, I was involved in a car crash and had to give up sport, which at that point was my life. During this time my godfather died, leaving me his camera and a book by the war photographer Don McCullin. And as I lay in hospital, I looked through this book – at stark, black-and-white photographs of the Vietnam war, of famine in Bangladesh, the war in Biafra – and I was so moved that I decided this was what I wanted to do with my life.

I taught myself photography lying in a hospital bed. By the time I was in my mid-twenties I was a rock photographer, travelling the world to capture bands and take fashion photography. I made a lot of money and I had great success, but as the years went on, I was incredibly unhappy and increasingly cynical about celebrity culture.

The turning point came in 2002 when – in the middle of a photoshoot – I threw my camera down on to a hotel bed, and it bounced out the window and smashed. It was, I thought, the end of my career. But eventually I began to think about how I could use my photography to help people, to advocate for them and tell their stories – a sort of activism with imagery. It made sense to me, and that’s really where my second life as a documentary photographer began.

I first had the idea for ‘Legacy of War’ in 2011. At the time I was mainly working with NGOs and charities – the Italian NGO Emergency, Médecins Sans Frontières and several others – to help tell their stories and those of the people they work with. I’m not a war photographer: if anything, I’m an anti-war photographer, and my interest has always been in what happens to countries when wars end.

My plan was to document the toll of war on civilians and the longer-term legacy – whether it’s displacement, or psychological and physical injuries – and perhaps, eventually, to help change the way we speak about conflict. Because if there's one thing my work has taught me, it’s that no matter where people are – Cambodia, Rwanda, Northern Ireland, Syria – the stories of those affected by war are the same. The themes are universal.

Afghanistan was to be the first part of the project. I was embedded with an American unit in Kandahar as I’d decided to do a story on the impact of war on soldiers. I felt it was important to record all sides of the conflict, and show how sometimes those fighting in a war can also become victims. Then one morning, while out on patrol, I stepped on a landmine.

The first few moments were bewilderment. I remember the blast; flying in the air and then thinking I was going to die quite quickly. My legs were blown clean off – I could see bits of them in the tree above me - and my left hand was shredded. I had one focus, and that was to stay alive for another minute, and then for another five minutes, and another. I was still conscious when they wheeled me into surgery.

I had 37 operations that first year. Four months later, I sat up in bed unaided. After a year, I began learning to walk again. I never questioned that I would get my life back: it’s all I kept saying and I was only annoyed that it took so long. Eighteen months later, I was back in Afghanistan and taking photos.

Is it hard? Yes. I am in physical pain every day, and it is exhausting. I don’t have the mobility I had: I can’t run and I can’t kneel. But it was very important to me to realise I could still achieve work of the same level. I would only do it if I felt I still had something to offer.

"The best photographs are never taken, they’re given."

"Each family has a different story. In that will be something people can relate to."

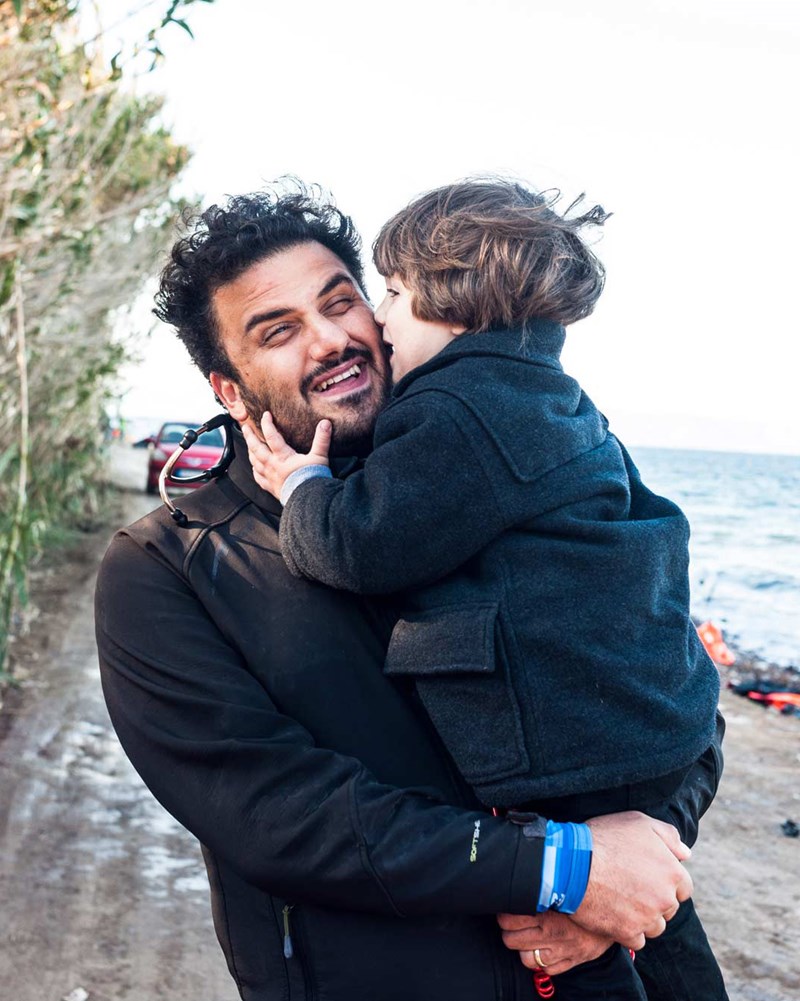

In 2015, I was approached by UNHCR to document the global refugee crisis. They gave me probably the greatest brief ever given to a photographer, which was “follow your heart”. I spent the next seven months crisscrossing Europe and the Middle East, from the beaches in Lesbos, to Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq, where the real crisis was taking place, finding stories and people to focus on.

When you have millions of people displaced by conflict, those statistics can become overwhelming. But each family has a different story, and within that will be something people can relate to. As a photographer, I’m very interested in intimacies – a father brushing his daughter’s hair, or a mother cooking for her children.

It’s little moments like that which are universal and sometimes, when the focus is on the horror of war, it distances us from that. My work is all about reminding us of the similarities. That it doesn’t matter whether you live in a refugee camp, or a penthouse, your intimate moments with those you love are identical.

Many of the families I’ve met have gone on to become part of my life. Shamah was a Syrian lady in her 90s, with a tattooed face, who was living in dire conditions in Jordan. When I turned up in her camp, she shook her finger at me, as if to say: “We don’t want a photographer here.’ And I couldn’t argue with that.

So I spent the next few days meeting people, talking to the families, and eventually I asked the community to help me set up my white sheet, which I carry with me to use as a backdrop. I turned away to fiddle with my cameras, and when I turned back, Shamah was standing there in front of the sheet. She was the first portrait. The best photographs are never taken, they’re given.

Months later, I sold that photograph as a print, and the money raised was sent to Shamah to buy a hearing aid she needed. So in the end it did bring her some help.

Khouloud I met in 2014. She, her husband and their four children were living in a makeshift, windowless tent in Lebanon’s Beqaa valley. Khouloud had been paralysed from the neck down by a sniper’s bullet, and her husband was her full-time carer: she couldn’t leave the bed.

When I returned in 2016, I remember showing her a photo I’d taken during my previous visit; of her husband Jamal sitting at the end of the bed, holding her hand – a photograph of love. But two years later, here they were in exactly the same position, and I remember bursting into tears and telling them I’d failed them because they'd trusted me with their story and still nothing had changed.

But this is the power of a story. That photograph was shared by an American charity called Random Acts, and they began crowdfunding money, using my photographs, and within the space of about two weeks we raised $250,000.

Earlier this year, we were able to use some of the money to move Kholoud into a new home in Lebanon, which has been adapted for her wheelchair. She has a garden now, and to see her and her husband’s face and the children running around, it makes it all worthwhile.

That’s the power of a story and I’m privileged that I get to tell them. Sometimes a photograph can change somebody’s life. — PA