Inequality begins at the school gate. That’s the belief of UAE-based businessman Faizal Kottikollon, founder of KEF Holdings and co-founder of the Faizal and Shabana Foundation (FSF), a private philanthropy focused on education and social development. It’s why, after raising $400m from the sale of his business in 2012, he decided to turn his attention and wealth towards rebuilding India’s underserved public schools in an effort to level the playing field for poorer students.

“Government schools are typically in a bad situation because they haven’t been properly maintained due to a lack of funding,” he explains. “Around 90 per cent of India’s kids go to these schools and that’s where the inequality starts. When they don’t have textbooks, or toilets, when the classrooms leak, you can imagine how that shapes them. It’s a chain reaction.”

In a bid to break that chain, Faizal and his wife, Shabana Faizal, have spent the past seven years studying, financing and delivering school improvement schemes in India, in addition to investing in social development.

Their foundation has donated more than INR340m ($4.5m) for the rehabilitation of schools, based on a model of quickly replacing crumbling classrooms with prefabricated structures.

The buildings are produced by KEF Katerra, a subsidiary of KEF Holdings, and are a fast-track way to revamp learning spaces and improve the condition of the school, without completely starting anew.

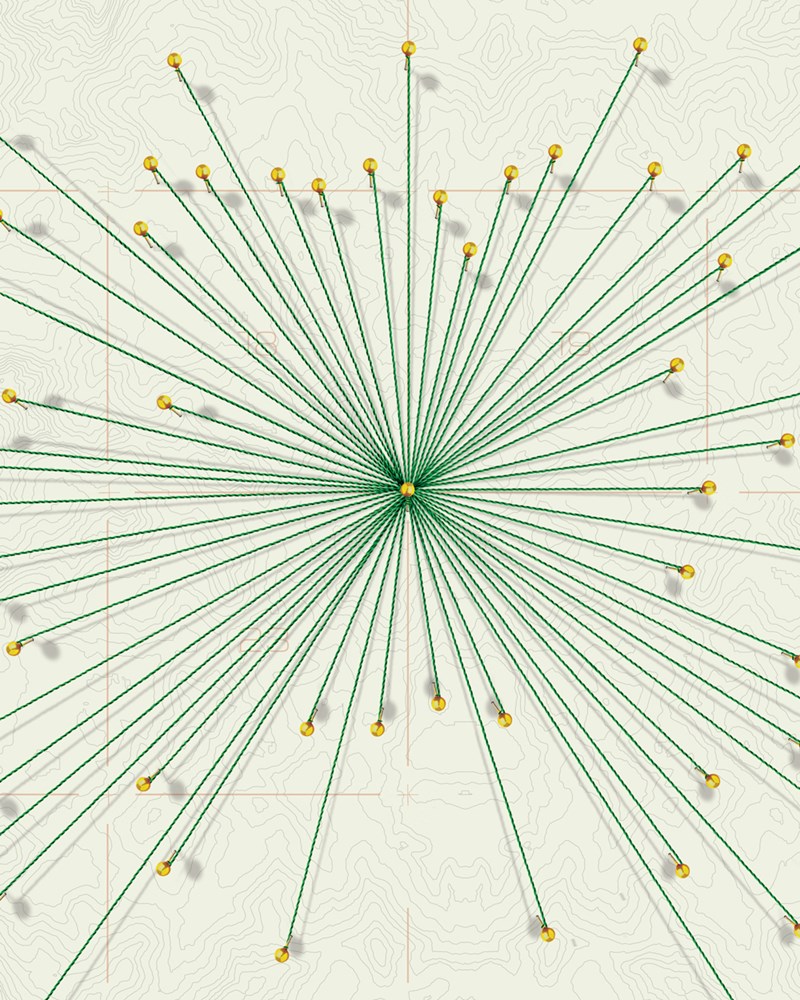

FSF has to date supported the renovation of 19 schools in three Indian states, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka, and the success of their model has seen it adopted by the Indian government. The practice has played a part in the transformation of nearly 1,000 schools countrywide, with more than 300,000 students benefitting from new classrooms and other facilities.

“What started out as pure philanthropy when we donated to our first school has now become a model for school renovation that is used across the country,” Faizal says.

1% Art and culture

1% Art and culture