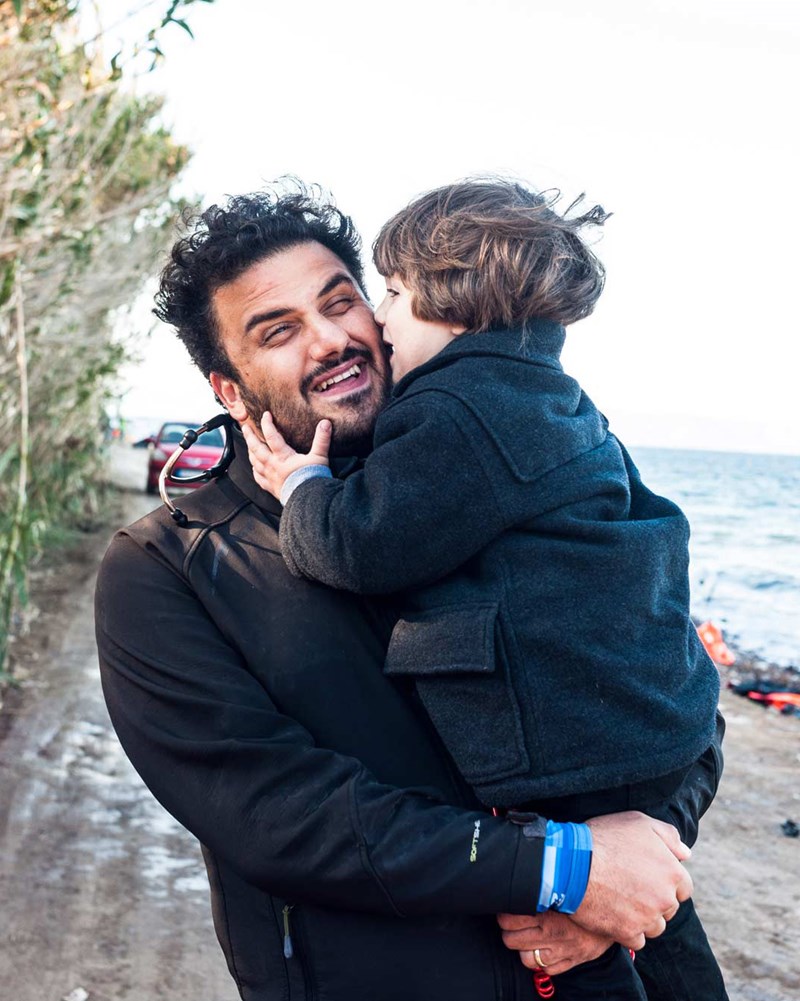

Of the litany of fears burdening Syrian refugees in the Middle East, the question of how they would feed their children was, until recently, not among them. Now it is. In September, the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP) said it would be slashing food aid to refugee families in Jordan due to a $278m gap in funding for the region. Those earning $2 or more a day would be cut from the aid programme in an effort to conserve funds for the most fragile; refugees existing on less than $1 a day.

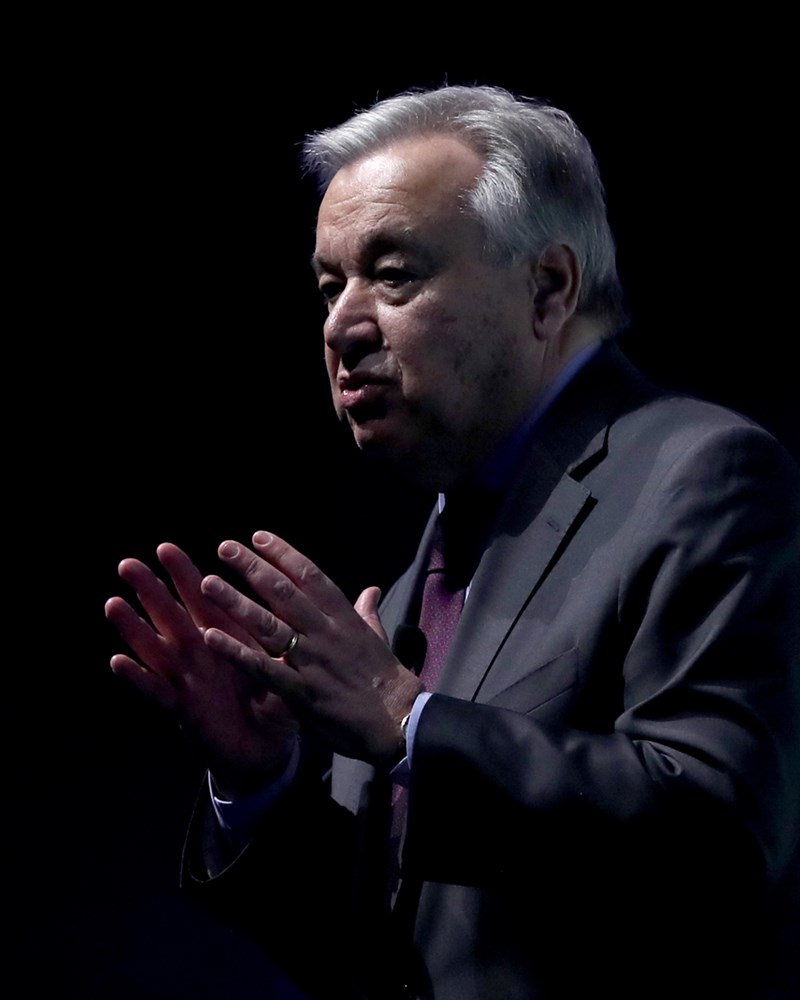

It is, says executive director Ertharin Cousin, an act of sifting the desperate from the more desperate. For the world’s largest humanitarian agency, it is also a matter of survival.

“When I talk to refugees now, they tell me stories about having to send their children out to work instead of school, because they are so worried about food,” Cousin says in a call from Rome. She’d returned hours earlier from Cairo, the final stop in a tour of the Middle East. “But this is the reality of the situation we face. We need additional funding.”

The WFP, the UN’s food-aid agency, is a safety net beneath the ranks of the global hungry. In 2014, it fed 80 million people in 82 countries – almost two-thirds of whom were children – doling out more than 3m tonnes of food-aid in the form of school meals, handouts and emergency relief.

On any given day, the agency has some 20 ships, 70 aircraft and 5,000 trucks in play, dispensing WFP-stamped rations to impoverished or disaster-struck communities around the globe. From Ethiopia, to Yemen, to Sudan and Pakistan: the WFP – for many of the world’s poorest – is the thin line separating them from starvation.

“Around the world, when we get it right; when we have the right resources and the capital, we can change lives,” says Cousin. “But how much assistance we can provide depends on how much money we receive.”