Counting the global zakat pot is a tricky business. Estimates of the scale of this form of Islamic giving vary wildly, from $76bn to in excess of $1trn, complicated by the fact that much of the money is dispensed through informal handouts to people or causes. “The numbers are very blurry,” says Houssam Chahin, UNHCR’s head of private sector partnerships in the Middle East and North Africa, “and not only in terms of how much is being raised, but where it is used and how.”

More widely agreed upon is the potential this giving has to change the face of global humanitarian aid. As a pillar of Islam, zakat requires observant Muslims to give the poor 2.5 per cent of the total value of their wealth each year. In some Islamic countries, including Indonesia and Saudi Arabia, it is collected by the state. Elsewhere, Muslims can choose to donate funds to the mosque, to charities or directly to needy individuals. Mobilised effectively, this capital could help plug the widening gap between development needs and financing – and impact millions of lives.

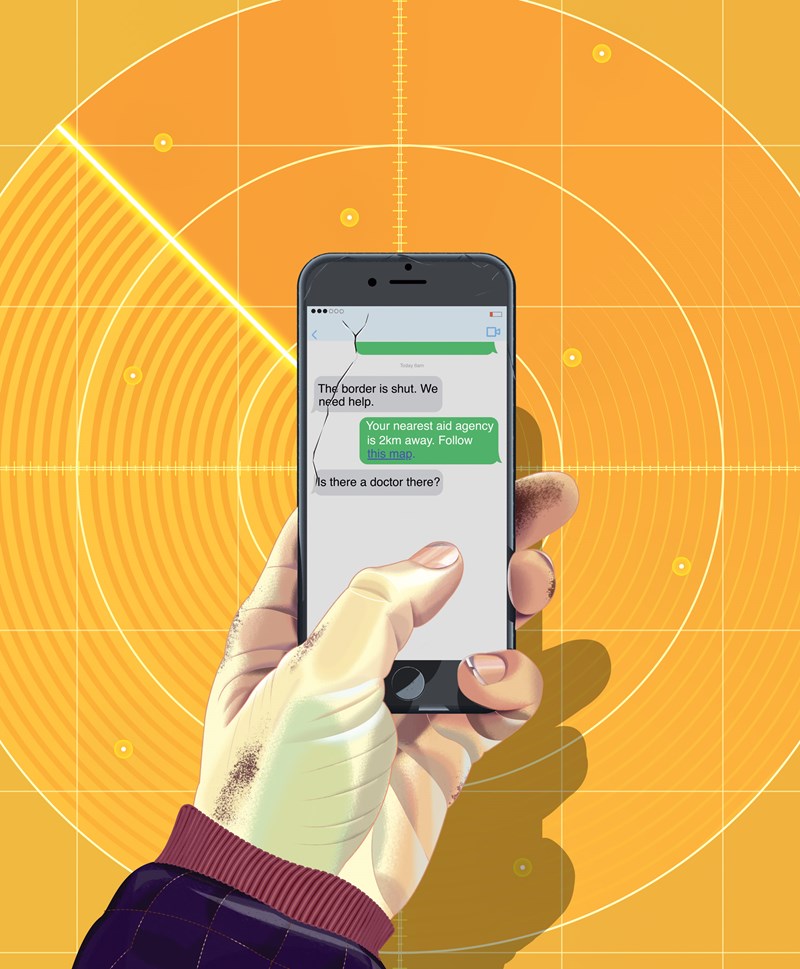

The UN refugee agency is among those working to tap Islamic giving through its digital zakat platform. Rebranded in April last year as the Refugee Zakat Fund, since 2016 the portal has funnelled donations to refugees and the forcibly displaced in Jordan, Lebanon, Yemen and Iraq. Bangladesh, Egypt and Mauritania have also been added to the list and in August last year, the inclusion of a sadaqah jariyah initiative (collecting Islamic alms donated voluntarily) extended the fund’s reach to in-need communities in South Sudan and Somalia.

The fund is UNHCR’s first high-profile foray into faith-based giving. Backed by five fatwas, and co-governed by the Abu Dhabi-based Tabah Foundation, it offers donors a digital and sharia-compliant giving channel that goes directly to those in need. Money is disbursed in the form of cash aid to families living in extreme poverty and donors can, if they wish, pick the cause their contribution is allocated to. The fund’s impact is shared via quarterly reports posted on the portal, which also offers a zakat calculator to help visitors determine their contributions.