Queuing at the bank is a familiar gripe, but for teachers at Aisha-i-Durani high school in Kabul, Afghanistan, it was the cost of getting paid. Each month they would wait for up to four hours to collect their salaries.If they didn’t reach the cashier’s desk by 1.30pm, they would return the next day to queue again.

Now they receive their wages at the ping of an SMS. They are part of a pilot project through which 500 teachers in Kabul use their mobile phones to receive salary payments. The scheme also provides them with a bank account, allowing access to other financial tools.

The group is part of a global digital payment, or m-money, revolution. In just six years, the industry has swelled to 82 million subscribers worldwide, with sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America leading the charge. It has been hailed as an example of how technology can be harnessed for the poor, to bring financial services within reach of the unbanked.

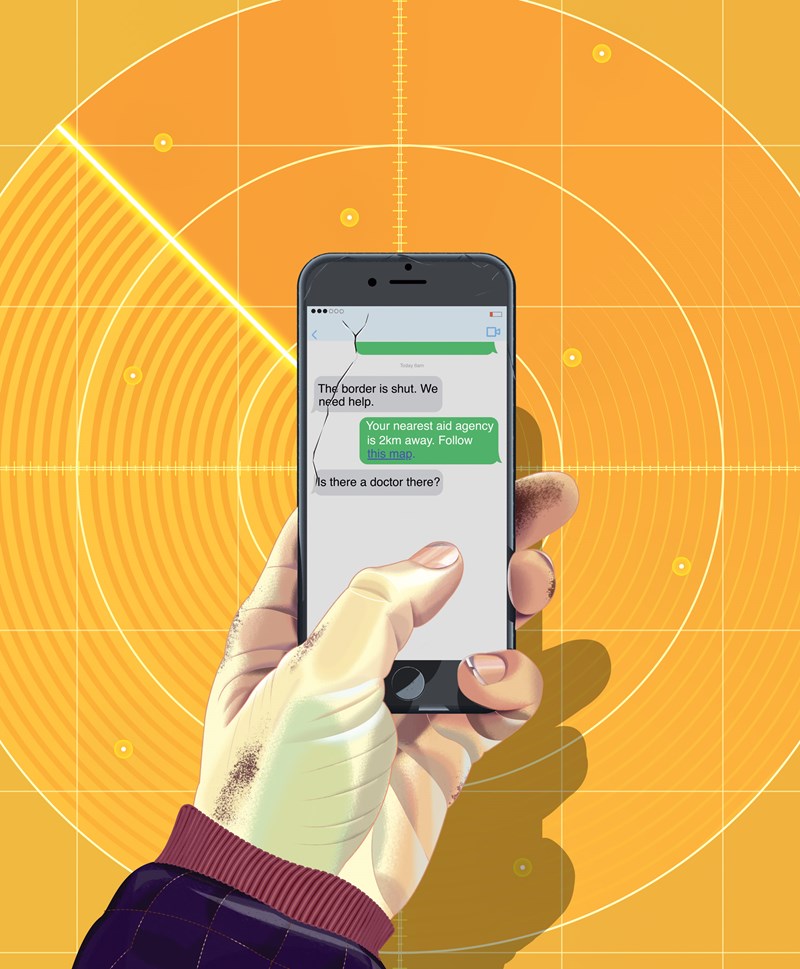

The concept is simple, but the impact significant. Mobile phones are used to perform banking functions quickly and cheaply, including paying bills, transferring cash to other users, and receiving funds. The idea is compatible with any phone: an agent deposits cash into a virtual wallet, and the recipient is sent an SMS alert and pin, allowing them to cash in the value.

The issue of financial inclusion is an acute one. One in two adults globally do not have a bank account, according to the World Bank. The Washington-based International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, estimates that banking services reach just 22 per cent of working adults in South Asia and 12 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa. Such limited inclusion is seen as a primary obstacle to economic development.

The world’s 2.5 billion unbanked are reliant on cash, which is easily lost or stolen, and can prove expensive to use for small transactions. Up to a quarter of savings are lost a year when cash is stockpiled at home, claims Tillman Bruett, manager of the mobile money for the poor programme at the UN’s Capital Development Fund (UNCDF). Paying bills by mobile phone can be up to 40 per cent cheaper than a bank visit, says Michael Wakileh, CEO of software firm ProgressSoft, which specialises in digital payment.

And these problems are if you can get money at all. “Putting a bank branch in a rural area where you don’t have a dense population is expensive. The beauty of mobile money is that it’s a lighter touch way to reach people,” says Greta Bull, programme lead for the IFC’s Partnership for Financial Inclusion.

Among the most successful digital payment models is Kenya’s M-Pesa service. Conceived for microfinance loan repayments, M-Pesa launched in 2007 and has enjoyed phenomenal growth. Some 70 per cent of Kenyan adults use it today, helping to drive financial inclusion levels in the African country from 41 per cent in 2009 to nearly 67 per cent today.

With similar underlying trends, poorer Arab countries are ripe for mobile money. A European Investment Bank study in 2012 of six Arab states, including Tunisia, Jordan and Egypt, found mobile penetration at 105 per cent. Access to finance, by comparison, was a meagre 36 per cent.

For these large, young and unbanked populations, mobile money could be used to transfer remittances and pay bills.