How would you characterise the global response, in terms of reaching refugees with education?

KW: I would say it’s been weak to non-existent. Very few countries have developed Covid-19 action plans for education that extend to refugees. There have been some initiatives – the Global Partnership for Education has done a bit more, the World Bank has done a bit more. But no-one has stood up and provided leadership for refugees globally, to say the international community will stand behind you and get you back into learning.

We didn't have a cohesive plan on refugee education before. And now, at a time when we desperately need one for recovery, it's not there.

In the absence of a unified response, what do you see as the most pressing challenges?

KW: We don’t have a full picture in terms of data, but I think it’s safe to assume well over half of refugees are currently not in a learning environment. So one obvious challenge is that these children need to be reached – whether through distance learning, radio learning, mobile libraries, or other options.

Secondly, beyond any focus on the classroom, refugees are living the reality of deepening poverty and worsening malnutrition. Hungry children do not make for good learners, so there is a poverty crisis that needs to be addressed.

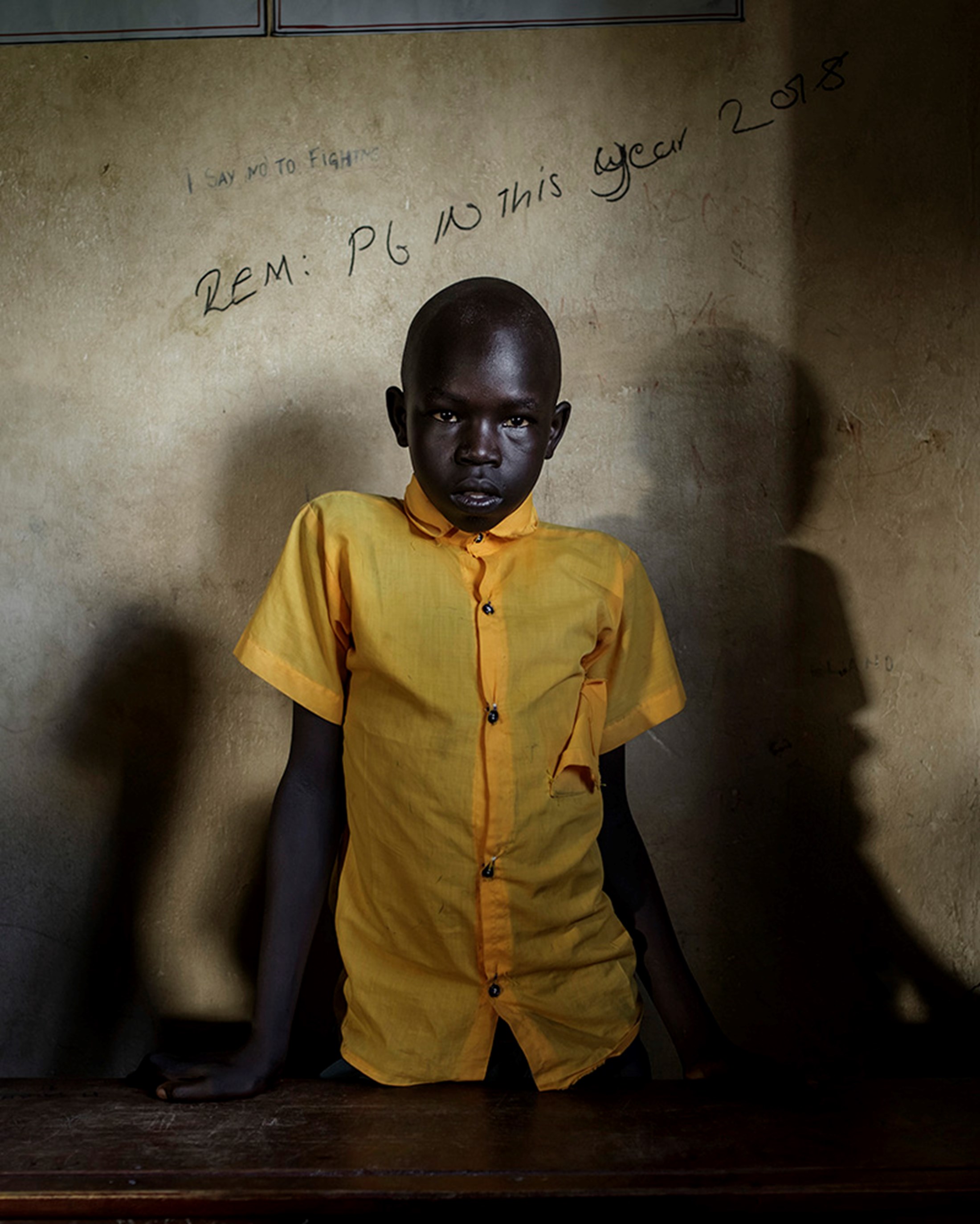

Finally, and this is a point that is much neglected, many of these children have been traumatised. This is the age of impunity, frankly, for committing crimes against children in war. We’ve seen it in Syria, we’ve seen it in South Sudan. These are children who often need trauma counselling to be able to learn.

Responding to these areas – we know it’s not necessarily rocket science. But it does need cohesive planning, financial commitment and political will. And all of these elements have been lacking, in my view.

SBJ: To look at the challenges holistically, we have 80 percent of refugees living on $3 a day in Jordan and Lebanon, according to UNHCR. There's a disproportionate effect on refugee children, particularly the most marginalised, which includes girls, working children and those with disabilities. It also highlights the cultural barriers at play. We see a higher risk of male dropouts; child marriage is rising again among girls – these are issues that are just piling on and on.

We need to think broadly. When you speak about refugees, I think it’s less than 2 per cent that go on to higher education. Of those that win the lottery and get a degree, they may not have access to employment in the places where they live. So for us, it’s not just about their getting an education – we also need to create pathways to elevated livelihoods, because that can be gamechanging for families and communities. Education is a piece of a much wider puzzle.

How do you build an end-to-end development response?

SBJ: We need cohesion between global and regional partners, and the private sector, and to bridge the gaps between education systems and labour markets. We need corporates to get on board with hiring refugees, and to acknowledge that if they are genuinely committed to achieving the SDGs [sustainable development goals], they need to act. We need everyone to have a seat at the table – governments, corporates, donors, NGOs – and to listen to the voices we are trying to serve.

We also need to see public education systems brought into the fold, because we want to see refugees included in national education systems for their own protection.

Has the pandemic presented any opportunities when it comes to scaling access to digital learning?

KW: It’s tempting to hunt out silver linings, but I would be cautious against over-egging the value of tech solutions to the education crisis. I find I am often bombarded with what purport to be great ideas – a Silicon Valley-designed app that promises to enable every refugee to become literate, for example. But that’s just not how education works. The relationship between the teacher, school, community and child is so important, and solutions tend to work when you really engage with a community to understand what is possible, and what the needs are.

What I would say is that we, and many others, have demonstrated in a micro way what is possible. Our Tree [Transforming Refugee Education towards Excellence] programme, for example, focuses on training teachers to improve the quality of learning and learning outcomes. It has a strong multiplier effect, because a teacher might be connected to 30 or 40 children, and – with online learning and support from national authorities – it’s something you can take to scale.

SBJ: I think the pandemic has highlighted that some ideas were held back because decision-makers weren’t ready to put their money into the use of IT as a tool. Equally, it has shown that access to broadband is a regulatory issue that needs attention – IT can’t be the only solution when so many don’t have access to the digital space. But where that has been taken seriously, it has the potential to work well.

Of the responses that we feel could be scaled, all are programmes that have been built on the ground for the communities they serve. The copy-paste approach does not work in educational development, because the culture, access to resources and context is so different in each location.

Grassroots solutions are driven by local partners – organisations that are often overlooked by global donors. Will Covid-19 change that dynamic?

KW: I think we all remember the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul, where the Grand Bargain made a commitment to put more money from donors into the hands of local responders. But donors put so many obstacles in the way of this happening. The reason so much money goes through UN agencies and international NGOs, is that donors want to transfer the risk elsewhere. As a result, the reporting requirements related to fiduciary risk are so complex, it’s impossible for local organisations to meet them. We talk about decolonising aid and decolonising development. but this is what is obstructing it.

We all have a role to play in solving this, Save the Children included. We need to do more.